Satanic Ritual Abuse myths and facts

When discussing Satanic ritual abuse, precisely defining what is Satanic ritual abuse can

be difficult. Often when alluding to it or describing it, references to infanticide, sexual orgies,

sexual torture of young children, blood baptisms, black robed figures, and confinement in coffins

is what is described. The horrific nature of the images often becomes the definition of what

“Satanic ritual abuse” is. The reality of the existence of this type of abuse is often ridiculed as

fantastical, too gruesome, or bizarre by detractors and because of that it does not exist, (Andrade,

G., & Camp Redondo, M., 2009; Matthew, L., & Barron, I. G., 2015). Therefore, the few vocal

advocates of ritual abuse survivors conclude that using horrific imagery to define a type of abuse

is imprecise, fails to capture the obstacles a survivor may face in recovery, and fails to lead

toward effective treatment for individuals claiming “Satanic ritual abuse” as their background,

(Badouk Epstein, O., Schwartz, J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011). In addition, some

researchers of Satanic ritual abuse decry the use of the word, “Satanic”, citing this type of abuse

can be found in every denomination and in organizations with no religious context and that using

the word, “Satanic”, induces discrimination against those who practice Satanism as their religion,

(Andrade, G., & Camp Redondo, M., 2009).

In defining more precisely what constitutes ritual abuse, some proponents of the reality of

this type of abuse focus on the manipulation of attachment needs, which is the abuse of

someone’s capacity for love and concern, as a defining characteristic, (Badouk Epstein, O.,

Schwartz, J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011). Researchers have recently suggested that

the “S” in SRA be dropped in recognition that ritual abuse happens with various groups and in a

variety of settings, (Andrade, G., & Camp Redondo, M., 2009; Ross, 2017). They further

demonstrate the differences between ritual abuse as a whole and groups that practice specifically

Satanic ritual abuse is that the practitioners of Satanic rituals have ceremonies that involve altars,

8

robes, goblets, ritual chanting, invocation of Satan, ritual sex with children, torture of children,

and sacrifice of children, (Ross, 2017). Satanism can be practiced without the abusive methods

imposed on women and children used in ritually abusive groups, (Andrade, G., & Camp

Redondo, M., 2009). The defining characteristics of ritual abuse are both more specific to the

techniques employed, the destructiveness of the abuse, and can also be generalized to groups of

any ideology, (Badouk Epstein, O., Schwartz, J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011; Ross,

2017; In Ross’s (2017) view what defines ritual abuse is that it is abuse that takes place in a

destructive cult with a charismatic leader. There is a hierarchy of initiates with an inner circle of

participants at the top, and there is extensive control over an individual’s life. If the individual is

not born into the cult, extensive recruitment strategies are used, (Ross, 2017). A hallmark aspect

of ritual abuse groups is that the questioning of doctrine in any form is synonymous with the

individual lacking faith or committment, (Badouk Epstein, O., Schwartz, J., & Wingfield

Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011; Ross, 2017). When this happens, specific techniques of control and

influence are employed such as: sensory isolation and deprivation, good cop/ bad cop strategies,

hypnosis, drugs, forced memorization of cult materials, the threat of death, sexual abuse, and

ceremonies to enforce submission and compliance, (Ross, 2017;Badouk Epstein, O., Schwartz,

J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011). Finally, the groups define outsiders as evil, ignorant,

and unenlightened, (Ross, 2017).

Although Colin Ross and other advocates of ritual abuse survivors use the word “cult”,

other researchers say that using the word “cult” further complicates establishing a precise

definition of ritual abuse. While many researchers in this field do use the word, “cult”, there is a

steady trend to not use this word in conjunction with ritual abuse because not all cults are

destructive, but all ritual abuse cults are destructive and abusive, (Dunn, S. E., Kaslow, N. J.,

9

Cucco, D., & Schwartz, A. C. (2017); Woody, W.D., 2009). Therefore, the term, “abusive

groups”, is gaining ground as a more precise term with which to refer to these types of groups,

(Woody, W.D., 2009).

A definition of ritual abuse which gives special attention to the manipulation of

attachment needs is given by Valerie Sinason (2011) of the Bowlby Center. This definition

attempts to give a more precise definition of ritual abuse and also avoids using the word “cult”:

A significant amount of abuse involves ritualistic behaviour, such as a specific date, time,

position, repeated sequence of actions. Ritual abuse, however, is the involvement of

children, who cannot give consent, in physical, psychological, emotional, sexual and

spiritual abuse which claim to relate the abuse to beliefs and settings of a religious,

magical or supernatural kind. Total unquestioning obedience in thought, word or action

is demanded of such a child, adolescent or adult under threat of punishment in this life

and in the afterlife for themselves, their families, helpers, or others. (p. 11)

It is ironic that the calls for a more precise definition of ritual abuse come from the

therapists who believe in and treat alleged survivors of ritual abuse. They claim that in order to

formulate better treatments, the exact nature of ritual abuse must be understood, (Badouk

Epstein, O., Schwartz, J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011). There seems to be agreement

among the different groups of therapists supportive of the ritual abuse narrative that the religious

and mystical symbols such as robes, altars, and goblets are less relevant and that what is

important to understand is the damage incurred from what was forced upon the victims in the

name of unquestioning obedience and loyalty to the abusive group, (Badouk Epstein, O.,

10

Schwartz, J., & Wingfield Schwartz, R. (Eds.), 2011; Ross 2017). In general, for the purposes of

this paper, the term ritual abuse will be used unless it is more historically accurate to use

“Satanic ritual abuse” or the reference of the abuse is specifically Satanic in nature.

Satanic Ritual Abuse: Historical Context

Is ritual abuse a new phenomenon? Some supporters of the existence of ritual abuse

believe that it existed long before 1980. Indeed, Satanic ritual abuse is discussed in the Old

Testament. While the Old Testament is considered a book of scripture for Christians, Jews, and

Muslims, it is also rendered a book of historical record by many scholars. One of the first

references to ritual abuse is found in Leviticus when the Lord makes it clear that the Israelites

just coming out of Egypt are to turn to the Lord and not to familiar spirits or wizards who

practice sorcery and necromancy, (King James Version, 1979, Leviticus 19:31). Necromancy, in

particular, holds significance when discussing Satanic ritual abuse because it was known to the

Israelites as a practice of black magic or witchcraft involving making marks upon dead bodies

and also the calling upon dead relatives in a ritual to seek for information, knowledge, or to

divine the future, (Elwell, 1997). The punishment for practising necromancy according to

Mosaic law was excommunication, and the practice for being a necromancer was the death

penalty, (King James Version, 1979, Leviticus 20:6; Leviticus 20:27).

Once the Israelites were out of Egypt and as they developed into their own independent

nation, the pagan religions that practiced these dark rituals and even darker rituals surrounded

them on every side in such countries as Moab, Phoenicia, Mesopotamia, Canaan, Syria, Assyria,

and others. The worship involving these rituals also involved many gods such as Baal, Baalim,

Molech, Milcom, Ashtoreth, and Asheriim. From the frequent admonitions and warnings from

11

God about abstaining from these practices it would seem Israel could not keep away from them.

The following are some examples:

There shall not be found among you anyone that maketh his son or daughter to pass

through the fire, or that useth divination, or is an observer of the times, or an enchanter,

or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a

necromancer, (King James Version, 1979, Deuteronomy 18: 9–12).

And when they shall say unto you, Seek unto them that have familiar spirits, and unto

wizards that peep, and that mutter: should not a people seek unto their God? For the

living to the dead, (King James Version, 1979, Isaiah 8:19)?

And he (Manasseh) did evil in the sight of the Lord, after the abominations of the

heathen, whom the Lord cast out before the children of Israel. For he built up the high

places which Hezekiah his father had destroyed; and he reared up alters for Baal, and

made a grove… And he made his son pass through the fire, and observed the times,

and used enchantments, and dealt with familiar spirits and wizards… , (King James

Version, 1979, 2 Kings 20: 2, 3, and 6).

In 2 Kings 23, in describing how Josiah got rid of all the supports and items of “idol

worship” and how he also tore down the places in which those ceremonies and rituals took place,

the writers reference the practices of sacrificing their children by fire, of ritual sodomy of men,

boys, and children, and of eating the blood, (King Kames Version, 1979, 2 Kings 23). Although

12

the groups practicing these rituals were seen as influences from the countries surrounding the

Israelites at the time, it was made clear to the Israelites that God considered the religions and

pagan practices of the Moabites, the Phonecians, and other countries to be not only an

abomination, but also originating from the “evil one” himself and were, therefore, Satanic rituals.

The concepts and doctrine found in the Old Testament become relevant to the explosion of

events that happened in the 1980s because much of the fear and panic generated from the news

stories and the autobiographical accounts of this extreme form of abuse was attributed to

Christian groups who saw these events as purely Satanic and emphatically labeled the extreme

abuse as “Satanic ritual abuse”, (King James Version, 1979; Andrade & Redondo, 2019).

Were stories of historical ritual abuse confined to ancient biblical times? Many

supporters of the existence of ritual abuse say it was found throughout the ages, located

everywhere, and found in a variety of religions and cultures, (Noblitt, J. R., & Noblitt, P. P.,

2014). David Frankfurter, a world religion and history researcher, gave compelling evidence of a

consistent thread of ritual abuse narratives throughout history in his book Evil Incarnate Rumors

of Demonic Conspiracy and Satanic Abuse in History, (Frankfurter, 2008) While he documents

the consistent thread of ritual abuse through time, he attributes the narrative to anthropological

constructs of “otherness” in cultures and scapegoating minority cultures within a larger society

instead of these narratives pointing toward actual events, (Frankfurter, 2008). The elements of

ritual abuse such as cannibalism, sexual perversion, sexual abuse and eating of children, blood

sacrifices, the drinking and eating of blood are found in second century accounts from Christian,

Jewish, and Zorastrian sources, (Frakfurter, 2008). An example from a 17th century patient’s

recollections of evil rites is remarkably similar to the autobiographies published in the 1980s and

1990s:

13

[The Christians, it is said,] actually reverence the genitalia of their director and high

priest, and adore his organs as parent of their being.… Details of the initiation of the

neophytes are revolting as they are notorious. An infant, cased in dough to deceive the

unsuspecting, is placed beside the person to be initiated. The novice is thereupon

induced to inflict what seem to be harmless blows upon the dough, and unintentionally

the infant is killed by his unsuspecting blows; the blood — oh, horrible — they lap up

greedily; the limbs they tear to pieces eagerly; and over the victim they make league and

covenant, and by complicity in guilt pledge themselves to mutual silence. Such sacred

rites are more foul than any sacrilege.

After [the priest of the witches’ Sabbat] has renounced his Creator, after having denied

Him and having watched a host of others follow his example, after having frolicked,

dancing obscenely and impudently, after having eaten at their festivities the heart of

some unbaptised baby stewed in violence, after a hundred thousand impudent,

sodomitic, and devilish copulations, … after having flayed a mass of toads to make and

sell poison and infected powders to destroy both men and harvests, he then added as

the final act of abomination the mockery of the most revered and precious Sacrament

that God gave to men to gain salvation.

The ceremonies had a congregation area facing a stage with an altar. There was a

procession down the main aisle from the back of the arena to the stage area. This

procession included the leaders of the cult, several adult women and children all dressed

in a variety of robes depending on their level of command. Once all were on stage, the

14

ceremony began, There was a service with chanting, the playing of drums in a beat of

changing rhythms, and the chief leader speaking and chanting. There was a door on the

back right side of the stone structure where children entered the stage. During the

ceremony children were to drink a drug-induced [sic] liquid from a large cup as part of

the service. The service continued to increase in intensity always resulting in the sexual

molestation of children on the altar and during some ceremonies the killing of those

children. …. During the services that were held outdoors in isolated mountain camps the

cult used torches and large bonfires to light the area. Fire was considered a special

expression of their religion and used to frighten the children by human sacrifices, burning

adults and children on large crosses, (Frankfurter, 2008).

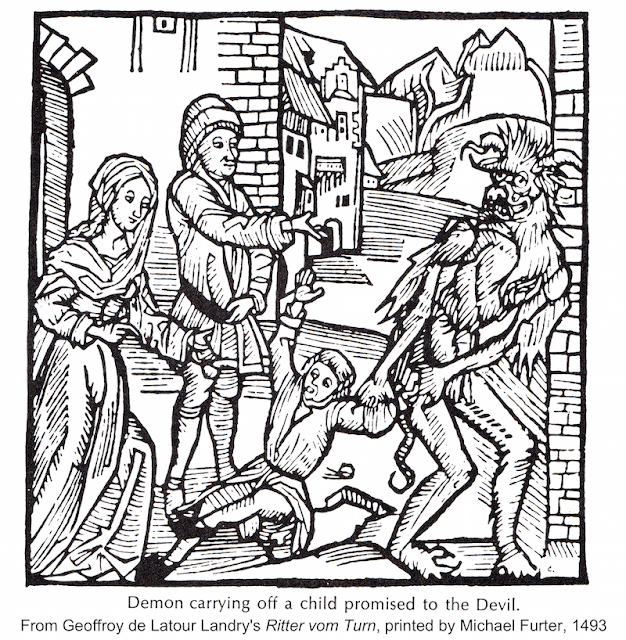

In addition to storied accounts, artworks throughout the ages

depict, in detail, similar rites and ceremonies of cannibalism, orgies,

and other grotesque rituals. Some artistic examples include Theodor de

Bry’s engravings from the 1600s such as scene of Tupinamba cannibals

and scene of sacrifice of a first-born child while women dance

(Frankfurt, 2008). De Goya’s “Black Paintings” depict disturbing

images of Black Sabbath rituals involving demonic dancing, erotic poses of naked men and

women, and the eating of human flesh. Another

15

pictorial demonstration involves the theme of necromancy in which a person by the name of

Edward Kelly is depicted communing with the dead in a

cemetery, (Sedgwick, 2020).

Ritual abuse themes are also not isolated to western

European nations; they also occur in Asian and African

populations, (Pietkiewicz & Lecoq-Baboche, 2017).

Quite often in many of these cultures, the majority of

the religious practices are innocuous, but for a minority

of priests and certain practitioners of the religions the

ceremonies become less innocuous and more violent,

(Noblitt & Noblitt, 2014). The beliefs associated with these darker, more violent practices often

have themes of power, healing, knowledge, and superiority, (Noblitt & Noblitt, 2014; Oksana,

2001; Pietkiewicz & Lecoq-Baboche, 2017). For instance, a South African group believes that

amputated body parts possess spiritual power, (Noblitt & Noblitt, 2014). In the Democratic

Republic of Congo witchdoctors are known to convey to some of their petitioners that raping a

virgin and gathering the defilement-related blood can strengthen the protection rituals given by

the witchdoctor, (Pietkiewicz & Lecoq-Baboche, 2017). The modern twist on this practice found

in the DRC is that raping a virgin can heal HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases,

(Pietkiewicz & Lecoq-Baboche, 2017). Finally, raping a virgin can provide the practitioner with

financial and economic power, (Pietkiewicz & Lecoq-Baboche, 2017).

Themes of attaining power and enlightenment through violence and sex is not only a

belief that is held today, but can be found historically. The most famous example is Aleister

Crowley who brought his brand of sex magick to the United States from Europe in the late

16

1800s, (Booth, 2000). Aleister Crowley believed there were three forms of sex magick;

autoerotic, heterosexual, and homosexual, (Drury, 2012). He claimed that by performing

specific sexual rituals, including sado masochistic sex rituals on young boys, one could achieve

financial gains and personal success, (Drury, 2012). For Crowley, the sex rituals were a

sacrament and ingesting the fluids from sex and certain biological functions, such as using

menstrual blood in rituals, would imbue him with knowledge, power, and success, (Drury, 2012).

Certainly, in creating a cult of personality with a devoted following and in being an influencer

through many generations, he can be considered successful.

One of those followers, possibly influenced by Crowley, is Paschal Beverly Randolph, a

mixed race medical doctor in Philadelphia in the 1800s. He is credited with introducing erotic

alchemy to the United States. Randolph considered himself a trance medium and he blended

many beliefs of the occult together for his own brand of sex magic which involved hetereosexual

and homosexual sex rituals.

Although Randolph is credited with establishing the first order of Rosicrucianism in the

United States, Johannes Kepler and his band of occultist Christians settled in Berks County,

Pennsylvania in the late 1600s were the first Rosicrucian sect in America. Rosicrucianism is a

secretive society with ties to ancient Egyptian and Arabic occult practices which were blended

into Christianity in the 1500s and 1600s in Germany. The Berks County Rosicrucian monks were

mostly isolated and would dress in red and black robes at specific times of the year such as the

summer solstice. They would chant and meditate and believed that meditation could bring about

healing for the body. While they mostly adhered to the teachings contained in the Bible, they also

believed they had secret knowledge of mystical importance and power and would practice many

gnostic traditions and rituals as well. While the Rosicrucian monks of Berks County,

17

Pennsylvania were thought to be a mostly peaceful band of people, they were mysterious and

secretive with their occult beliefs forming a major part of their religious practice. Paschal

Beverly Randolph chose to incorporate many of their beliefs and practices into his own sex

magic practices and when establishing the first Rosicrucian order in the United States.

As Aleister Crowley’s cult of personality began to die off in the 1940s, another in the

1960s took its place. Anton LaVey, born in 1930, not only considered himself a Satanist, but

established The Church of Satan as a religion in the 1960s. (Crowley, though often accused of

being a Satanist, did not consider himself to be one.) Anton LaVey wrote the Satanic Bible in

1966, The Satanic Rituals in 1972, and The Satanic Witch in 1989. It is unclear which of the

stories about his life are true or fabricated because, much like his predecessor, his greatest

personal asset was his charisma and his ability to create a cult of personality. He was, at least on

the surface, committed to the religion he created as demonstrated by naming one of his children,

Satan, and when he died he was given a private Satanic funeral before his cremation.

Many of the followers within the Church of Satan practice Satanism mixing in Ayn Rand

and Nietzschean philosophies with the more benign rituals found within the Satanic Bible. There

are other groups who practice the Satanic rituals found in LaVey’s works in a less benign way, or

even along darker and more violent methods of ritualistic abuse.

The consistent narrative of ritual abuse throughout the ages, beginning with the Old

Testament labeling it as evil and of Satan, the rise of The Church of Satan in the 1960s and

LaVey’s works circulating throughout the world, combined with the feminist psychology of the

1970s, which brought into the public discussion child abuse within the home including the

molestation of children, provided a perfect contextual backdrop for the explosion of Satanic

ritual abuse into the public discussion in the 1980s.

Post a Comment